News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

Working paper examines employment, marriage prospects and financial security

November 05, 2018

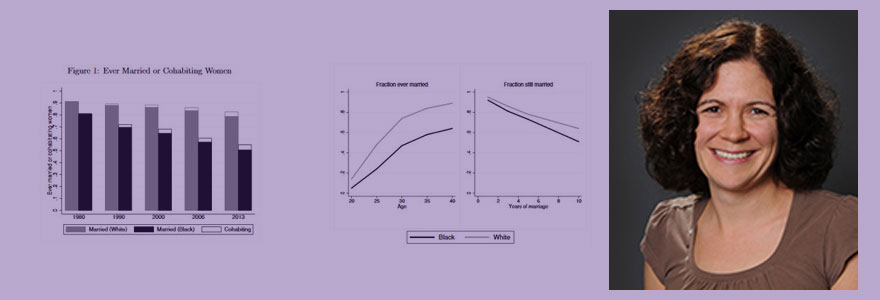

The marriage gap between white and black women in the US is growing, and this may have long-lasting impacts.

While 83 per cent of white women between ages 25 and 54 were ever married in 2006, only 56 per cent of black women were: a gap of 27 percentage points.

‘Is Marriage for White People? Incarceration, Unemployment, and the Racial Marriage Divide’, a new working paper by Elizabeth Caucutt, associate professor of Economics at Western University, Nezih Guner, CEMFI, and Christopher Rauh, assistant professor at the University of Montreal, looks at some of the reasons for the increasing disparity.

The researchers pin-pointed a few key aspects affecting the marriage rates between white and black women.

Due to an increased chance of premature death facing black men, there are 15 per cent more black women than men in the US population. This combined with incarceration rates that are around five times higher for black men decreases the chances a black woman will meet someone to marry. When they meet, high unemployment and incarceration rates among black men contribute to lower marriage rates among the black population. This was originally highlighted in the Wilson Hypothesis in 1987.

Caucutt and her colleagues built on the original Wilson hypothesis, developing a dynamic picture, accounting for different probabilities of unemployment and incarceration in the population.

Their analysis showed that higher incarceration and unemployment rates account for around half of the racial difference in marriage rates.

Employment had a much greater impact, with black Americans disproportionately affected by a decline in manufacturing jobs.

“Employment prospects seem to be the most important for racial differences in marriage rates,” said Caucutt. “If men are unemployed or precariously employed, they are less likely to be married, and less likely to be considered appropriate to marry.”

Marriage can provide economic benefits through coordination of resources such as sharing costs of housing, utilities and food. It can also provide security and insurance as people age; single women who never marry are more likely to live in poverty.

The benefits of marriage extend to the next generation as well. “If a child is born into a two-parent household, versus a one-parent household, there can be a big difference in investment in things like education,” said Caucutt.

“I’m not saying everyone should be married,” said Caucutt. “What we want to do in this work is to understand the marriage decision and its relationship with policy. For instance, we find that increased incarceration for drug offenses accounts for around four per cent of the racial marriage gap.”

While there has been a decline in marriage rates across the general population, some of this has been replaced with cohabitation. Caucutt says adding cohabitation to marriage does not lessen the racial gap.

The marriage gap, Caucutt says, is a recent phenomenon. “In the 1950s and 1960s, marriage rates were similar between white and black populations,” said Caucutt. “In our model, it is not a cultural issue; there is no preference difference for marriage among groups.”

Caucutt plans to continue this work, with further research into the impact of marriage rates on children, and potential policy implications.