News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

What does Conservation Look Like in the Anthropocene?

October 30, 2018

Does human activity always lead to less bio-diversity? Not necessarily, says Paul Robbins.

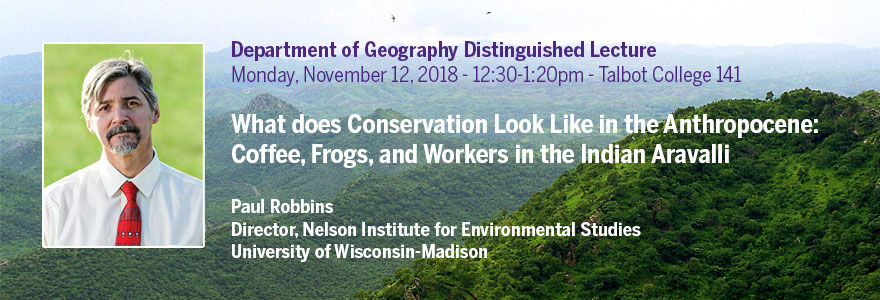

Robbins is Director of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. On November 12, Robbins will present the Western University Department of Geography Distinguished Lecture, entitled “What does Conservation Look Like in the Anthropocene: Coffee, Frogs, and Workers in the Indian Aravalli.”

Robbins has investigated the level of bio-diversity in the Indian Aravalli, an area he describes as the “battery of bio-diversity for south Asia”. The area has been settled by people and heavily used for agriculture for a long time, yet is still teeming with a wide-variety of wildlife.

Through a focus on counts of amphibians and birds, and through surveys of farmers and farm-labourers, Robbins and two other researchers, an agricultural economist and a conservation biologist set out to determine what made some areas more bio-diverse than others.

“Can people cultivate wild-life, or are people always the kiss of death?” said Robbins.

Robbins said the existence of bio-diversity in the area is largely an “accidental outcome of what the farmers are doing.”

Coffee plantations can lead to bio-diversity through the use and existence of a shade canopy, but commodity and labour markets can play a significant role in determining the levels of bio-diversity.

If there was fewer people available to do farm labour, coffee farmers in particular change their farming practices, moving to open the canopy and using more pesticides.

Similarly, a market preference for Robusta coffee over Arabica coffee would lead to increased intensification, a change in the forest canopy and more harmful farming practices.

While labour shortages may lead to an increase in wages, the associated changes in farming practises in turn, meant there was less bio-diversity.

“What’s good for workers isn’t necessarily good for the landscape,” said Robbins.

Robbins suggests there may be ways to create benefits for both workers and the environment, through coffee brands focused on conservation and sustainable practices. This, however, requires buy in and interest from the consumer.

The situation and questions presented in the Aravalli may be repeated on around the world. By 2050, population growth rate will level off, with most people living in cities, and less people, and labour, available in agricultural areas, Robbins said.

“What does agriculture look like in a labour poor, but energy rich world?” asked Robbins. “Does this mean more mechanization? This is a world-wide question.”

From an environmental stand-point, Robbins said there is the possibility of having lots of bio-diversity where there is a large population.

“It’s not like people are going away,” said Robbins. “How can you create a mosaic in a human-dominated world? There are ways; we got it in coffee farming by accident. Imagine what we can do if we tried.”

The Department of Geography Distinguished Lecture, featuring Paul Robbins will be on Monday, November 12, at 12:30 pm in Talbot College, Room 141.