News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

Aging population leading to divergent health and social outcomes, Margolis finds

October 20, 2017

Across Canada and the United States, people are living longer, and their social networks and activities have a major impact on their quality of life.

Rachel Margolis, Associate Professor of Sociology at Western University, has had research papers published recently that look at how the quality of life of older adults differs based on the number and types of available kin.

Working with Ashton Verdery of Pennsylvania State University, Margolis found that the number of older adults without close kin, (e.g. spouse/partner and children; or spouse/partner, children, siblings and parents) is increasing in the United States, most noticeably among non-Hispanic Black women.

The pair found that today, kinless-ness is most common among college educated women and men in the lowest education levels. It is also more common among those with social, economic and health risks. Margolis said that it is not clear that one causes the other, but did point out that those who are kinless are more likely to be socially isolated, have lower income, and to rely on social programs and institutional care.

People without kin, Margolis added, are also unlikely to have advocates for their care if they do end up in institutional care.

Margolis said there are many factors contributing to increases in the rate of kinless-ness in older adults, including recent declines in marriage rates, increases in ‘grey-divorce’ and fertility declines, all leading to larger number of older adults with no close family members. Population aging is also important for increasing the numbers of older adults who are likely to be without close kin.

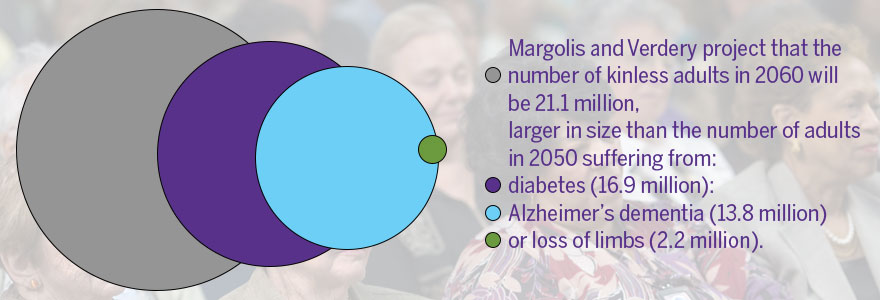

The researchers note that the increase of kinless-ness is of a similar magnitude as the other notable chronic diseases. Margolis and Verdery project that the number of kinless adults in 2060 will be 21.1 million, larger in size than the number of adults suffering from diabetes (16.9 million), Alzheimer’s dementia (13.8 million) or loss of limbs (2.2 million) in 2050.

With the previously noted connection with poorer health, Margolis and Verdery conclude that the trend represents a potentially critical issue “for society as a whole, institutions that provide services for older adults, and the kinless themselves.”

“We’re thinking about how big of a problem this is, about types of kinless-ness that are expected in older age and types that are unexpected. If you are never married and never have children, in a certain sense, you know you’re not going to have that kind of kin when you are older and you can prepare for it a bit more,” Margolis said.

“One big implication of this is for health systems. Often, hospitals and other types of health-care organizations are billed and organized such that family members are expected to take care of people when they leave the hospital. If there are no kin nearby, available to take care of someone, then people are often taking up hospital beds.”

In an upcoming study, Margolis will compare kinless-ness and the well-being of adults without family members in Canada and Europe to those in the United States.

Older Adults With Close Kin in the United States was published in the Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. Projectionss of white and black older adults without living kin in the United States, 2015 to 2060 was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

In another recent study, Margolis found that older adults are living longer, lengthening the period of their lives they may be grandparents. With improvements in health care, they are often living healthier, more active lives, and are more involved in the lives of their grandparents, as compared to previous generations.

Margolis’ study found that middle-aged dads can now expect to be grandparents for 19 years, with at least 14 of those years as “healthy” grandparents. Mothers can expect to be grandmothers for 23 years -- the majority of it healthy. That long period is allowing many grandparents to live long enough to build close and lasting relationships with their grandchildren.

Margolis spoke with CTV News about this study.