News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

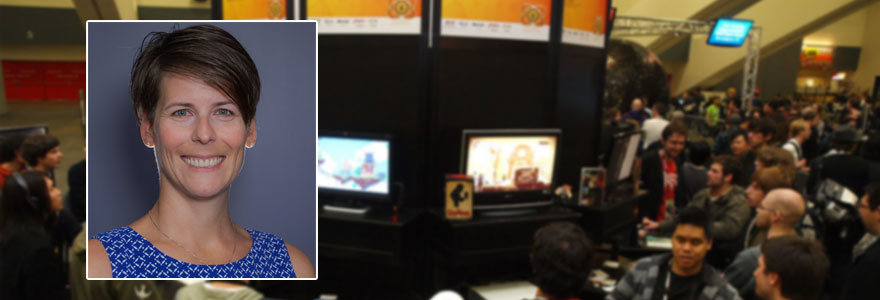

Developing organized labour in the game industry

July 16, 2019

Precarious employment, long work hours, digitization of labour, these are some of the challenges facing people working in the video game industry.

Johanna Weststar is an Associate Professor in the DAN Department of Management and Organizational Studies. She has been studying the working conditions in the video game industry for 10 years. While most research in labour relations and management focuses on more traditional industries, such as manufacturing or the public sector, Weststar is interested in video game development as a new and emerging industry.

Weststar sees the game industry as an example of the challenges facing many workers in a changing economy. As the industry matures, workers are taking more concrete steps to organize and demand rights.

In a recent paper, Building Momentum for Collectivity in the Digital Game Community, Weststar outlines the approaches game developers have taken to improve their workplace situations. Weststar will also be participating in a public forum on the issue in Toronto, entitled Remaking Game Work to discuss these issues.

Initial efforts took the form of protests, such as secret messages added to games, creating Easter Eggs for players to find, which would give credit to the studio workers who completed the game. As consumers found these, they began to like them more and the industry co-opted them.

The next stage of activism took the form of increased discussion about the issues workers faced. This included the development of a professional association and more discussion of quality-of-life issues developers faced.

These approaches were complicated by the attachment many developers have to the industry. As many played games as youth, they often identify themselves as ‘gamers’ and feel more connected to the industry.

“The industry relies on a lot of fresh, passionate and typically young, male workers,” said Weststar. This connection along with the way project-based work is structured and managed, Weststar said, leads workers to ‘self-exploit’, working long hours to meet deadlines they cannot control.

“They are making fantastical creations, but it’s hard work and takes a toll,” said Weststar.

The approach to making video games creates its own set of challenges for workers. While publishers put games out, they contract game development studios to build the games. Publishers set the timelines, and the studios have to meet the demands. This means that developers are largely powerless to change the timeline, and demand more from their workers, often creating time-crunch situations.

After the projects are complete, the studios must find other work. This means that, for many workers, when the project is done, their job could be gone, creating an environment where employment insecurity is the norm.

In recent years, workers have taken steps toward more organized resistance, raising their voices in two parallel streams: improving working conditions, and addressing sexism and the representation of women.

There has been an increase in talks at major industry conferences to deal with the issues and workers are beginning to organize their own groups, as a possible precursor to forming unions.

Once such group is Game Workers Unite, which has tailored its message specifically to the community, and is in talks with existing unions.

Weststar is interested in following the development of GWU, as a case-study of the efforts to improve working conditions in contemporary workplaces through innovative forms of worker representation.

“Now is a pivotal time to see where it is going,” said Weststar. “It will be interesting to see what workers can gain and whether these changes can stick.”