News and Updates

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

Reconciliation can help address global problems, but first we need to deal with white supremacy

February 25, 2022

For many Indigenous people in Canada, reconciliation is dead. This should be deeply concerning for all Canadians. Sadly, it’s not.

Settler colonial governments and mainstream Canadian society are consistently failing to connect the dots between issues like missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people and the soaring rate of Indigenous youth suicide — which are still seen as part of the “ aboriginal problem” — to broader societal challenges such as climate and ecological degradation.

These issues are closely related, and their common denominator is white supremacy. Reconciliation can help solve many global problems, but white supremacy is currently one of its biggest threats. To move forward we should look to Indigenous place-based practices.

I am an Indigenous, feminist scholar and activist of Ngāi Te Rangi (Māori), Scottish, Welsh and German ancestry from Aotearoa. I grew up disconnected from my tribal roots but have devoted much of the past two decades reconnecting to my traditional territory and tribe. I recently wrote a book about Indigenous-led intergenerational resilience, which forms the backbone of this article.

White supremacy

White supremacy is about the power, privilege and patterns of individualist, binary and hierarchical thinking associated with, but no longer exclusive to, white people.

The alignment of white supremacist ideas with neoliberalism and rising global corporate power means that lands and bodies are increasingly seen as disposable.

This is evident through the Kentucky candle factory disaster that claimed the lives of the 74 workers who were denied permission to leave their work stations and go to safety during an impending climate emergency.

The government’s wind down of the inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls — despite women and girls’ ongoing trafficking into “ man camps” for sex services — is an example of how corporate interests dominate decision-making.

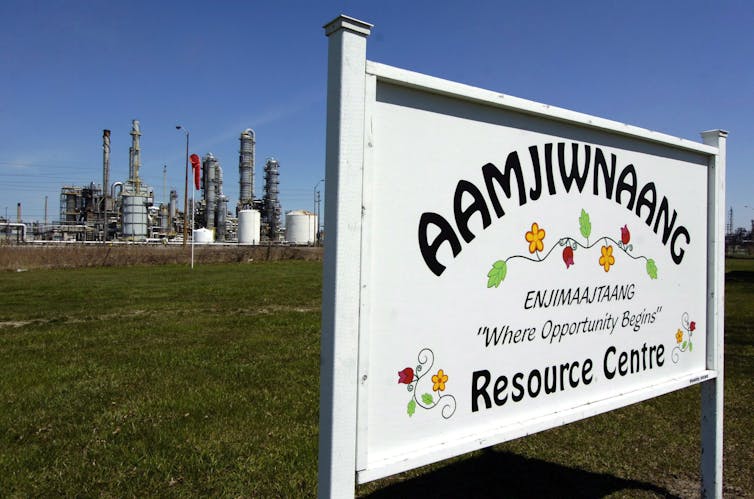

The government-sanctioned poisoning of Aamjiwnaang First Nation, whose lands lie in the heart of “chemical valley” — is yet another tragic example of the sacrifice of lands and bodies to corporate interests.

White supremacist structures and patterns of thinking also underlie the overtly techno-rationalist — an overemphasis on western science and ways of knowing that rely on the application of technology to fix problems — approach to climate catastrophe and the corporatization of the renewable energy sector.

This has resulted in an emphasis on market-driven goals of climate prosperity that prioritize profit and ends up replicating racialized, gendered and species hierarchies, oppressing certain groups.

Implementation of UNDRIP

The global challenges we face are complex, interdependent and require Indigenous intercultural and intergenerational decision-making to find a solution.

Reconciliation requires a re-prioritization of knowledge systems and it will take a collective effort grounded in the resilience and knowledge of place to make any visible difference.

The implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) within Canadian legislation could be a beacon for this country.

Ultimately, UNDRIP calls the “ the long ago colonized” and those who are intergenerationally disconnected from their traditional territories and peoples, to reconcile with the Indigenous legal orders of the land.

One way of supporting this is through the following Indigenous-led intergenerational resilience practices:

- Focus on reclaiming our fundamental human capacity to be of place.

- Centre Indigenous legal orders and leadership.

- Be inclusive, intergenerational and culturally situated.

Indigenous intergenerational resilience is about coming to belong through ethical relationality. This involves treating our more than human relatives (the waters, trees, rocks) as our Elders and taking on the responsibility of looking after them.

An example of Indigenous-led intergenerational resilience is land-based learning that privileges the Indigenous traditional knowledge and stories of place, while at the same time inviting others to contribute relevant stories or experiences from their own cultures. People learn best when they are in their own cultural skin.

Learning rooted in place

In an age of continuing Indigenous erasure, an invitation to collective belonging can be risky for Indigenous Peoples because of the overriding tendency for settler laws, identities and ways of thinking to further erase Indigenous Peoples and lifestyles.

For Māori — the Indigenous Peoples of Aotearoa — this practice, or tūrangawaewae (standing place), is achieved when a person defines their identity by linking themselves to their tribe, their environment and their Indigenous knowledge base. Once achieved however, tūrangawaewae is not a given, and relies on the continuation of kinship practices.

Te ahi kā , the Māori concept that means burning fires, meanwhile, denotes the continuance of these kinship practices.

According to Tuhoe (Māori) scholar William Doherty “ ahi kā” expresses continual connection to the land. If a person does not live within their territory or maintain their kinship connections, their ahi kā is deemed “ matao” or cold. For a person to re-establish their ahi kā, they have to serve a period of apprenticeship, regardless of their position held before the period of absence.

Ahi kā roots reconciliation in the land and provides guidance to those who are disconnected from their lands and communities. It also offers a way forward for those who aren’t Indigenous to Canada.

Turangawaewae would be earned through apprenticeship to the Indigenous knowledge keepers of a territory. During this process, participants would learn about the Indigenous laws of the land on which they are guests.

If guided by the knowledge of the land, reconciliation will also eventually address the seemingly uncontrollable and interrelated global problems of climate crisis, interspecies displacement, gendered and racialized violence and white supremacist structures. Ultimately, it will heal our condition of human “disconnection.” ![]()

Lewis Williams, Associate Professor, Indigenous and Environmental Studies, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.