About Us

Contact

Faculty of Social Science

Social Science Centre

Room 9438

Western University

T. 519-661-2053

F. 519-661-3868

E. social-science@uwo.ca

Shatzmiller Hellmuth Prize Acceptance speech

Maya Shatzmiller, professor in the Department of History, was awarded the 2018 Hellmuth Prize for Achievement in Research, in recognition of her ground-breaking research that has challenged widely-held assumptions about the medieval Islamic world.

Shatzmiller has studied Arabic chronicles and compiled numeric data relating to economic markers, such as the price of commodities, amount of coinage in circulation, exchange rates, and cost of goods. Using the data, she demonstrates that the medieval Islamic world functioned well, producing wealth and a standard of living higher than anywhere else in the world at the time.

The Use and Abuse of Economic History: The Case of the Islamic Middle East

Introduction: What is it that I do and why?

I am an economic historian of the Islamic Middle East. I study the production of wealth and its distribution to members of medieval Islamic societies, using empirical evidence derived from the Arabic sources, through applications of economics methodologies. Bishop Hellmuth could not have guessed that this unusual subject will be studied and taught at Western, but then, he was a man of religion and a humanist, and I believe he could relate to what I am about to say today. I am proud to associate my name to his.

Why medieval Islam? Medieval Muslims were literate and numerate. They translated Greek, Roman, Persian, and Indian works of science, technology, philosophy, mathematics, medicine and astronomy into Arabic. They studied and renewed civil engineering and military technology, among others. They were humanists, interested in world history and geography, and in other peoples’ literature. There was hardly an intellectual discipline they were not interested in and to which they did not contribute. Furthermore, they efficiently transmitted old and new knowledge by perfecting the manufacturing of Islamic paper and producing books in large volumes in the codex format – like those you can see in this image:

Europeans waited 500 years in the ‘dark ages’ for the knowledge of Greek sciences, technology, philosophy and medicine to come to them in Arabic translation. Without the mediation of Muslim scholars, Greek knowledge may have been lost to humanity. I study the economic underpinnings, foundations, and developments which made these achievements possible. These intellectual and civilizational accomplishments were made possible thanks to an unusual economic development in the medieval Middle East and the vibrant economy that followed. I devote my time to studying the reasons for the change in economic structures and to the developments that ensued.

The Challenge: Assembling the Data

Medieval historians need to have the linguistic skills to retrieve the evidence from the sources but medieval economic historians also need to use the statistical applications and theoretical insights from economics. And for that the data needs to be assembled. Studying the economic history of the medieval Islamic lands presents special challenges: Empirical evidence comes from the many chronicles which survived in manuscript form, but little statistical evidence is available, and none was ever collected in a systematic way. No time series for example, which is data needed to study economic indicators. I had to start from zero. For the last 15 years, I have collected statistical data from the Arabic sources to reconstruct the medieval economy and process it according to current standards.

The Medieval Islamic Economy Database

On this site, you will find a database containing commodities prices, wages, money and weights, indicators of living standards, taxation, national accounting, and other statistical data, and all that is needed to make sense of what it all means. Two examples that stemmed from the findings will illustrate the importance of the database: first, determination of living standards in the Middle East; second, the endogeneity of women’s property rights.

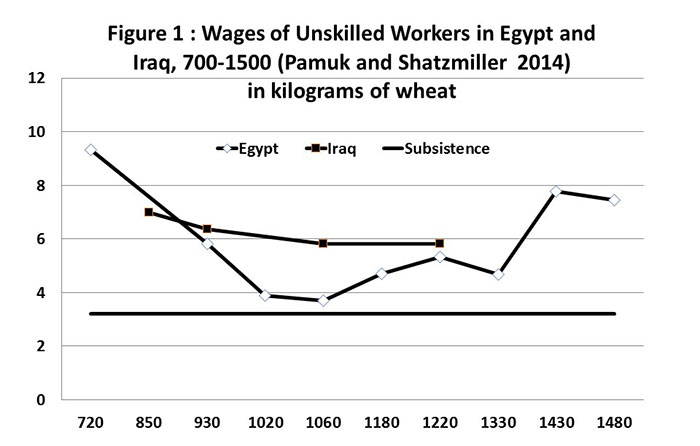

The graph illustrates standards of living in the Middle East as determined by their purchasing power. It shows that living standards were ‘high’, both primarily and comparatively among contemporary economies. What you see on the graph is the extent of the purchasing power of wages of unskilled workers. The solid line in the graph represents the subsistence level and the fluctuating one represents wages of construction workers in medieval Iraq and Egypt between 700-1500. The graph demonstrates that these workers, the lowest group among wage earners, earned wages that were twice or three times the subsistence level, quite extraordinary for medieval societies. The high wages in the Middle East were likely the outcome of a tight labour market in the aftermath of a major demographic catastrophe, the Justinian plague. This and other structural changes improved economic performance in the early Islamic Middle East. In addition to the effect of Justinian plague, economic theory also suggests that changes in economic structures and institutions will affect economic performance. Structural change in property rights, in population levels, and in division of labour through technological progress, explain our findings.

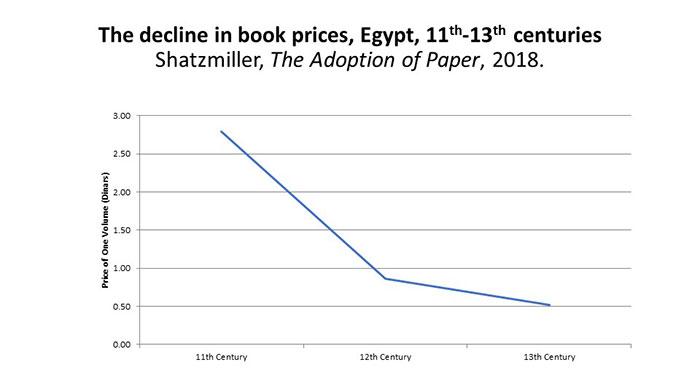

Another manifestation of the high purchasing power of wages comes when the data on wages of construction workers is compared to data on the price of books. I ask how many day’s wages were required for purchasing a book in a way to account for human capital formation. By comparing the number of day’s wages required to purchase a book to a new database of book prices, I found a considerable decline in the number of day’s wages. Further research on the components of book production suggests that the price of books went down thanks to decline in the cost of production of Arabic paper and the easy diffusion of paper making techniques, making it possible for more workers to purchase more books on stable income. The findings determine the existence of a correlation between purchasing power of wages and human capital formation, eventually contributing to higher productivity.

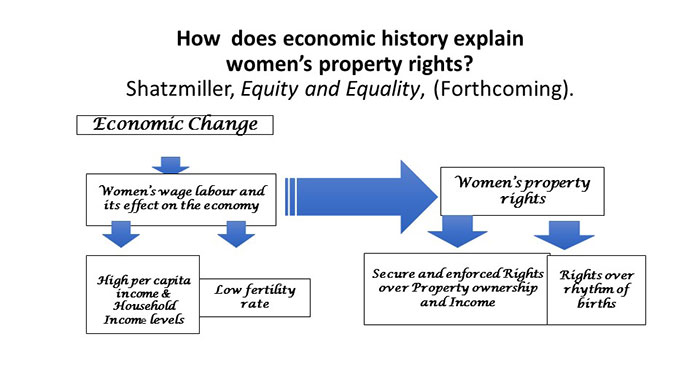

Finally, economic history can play a role in diffusing misconceptions about women and Islam. The idea that Islamic law, shari’ah, discriminated against women is false. Islamic law gave women the rights to own property and transact with it by giving them complete and unrestricted property rights. Completely free of intervention from their husbands, there is no conjugal property in the Islamic marriage. Wives inherit and bequeath freely, receive gifts, keep their wages and make endowments. Shari’ah law did not develop in a vacuum. Indeed, laws responded to the same economic change that raised wages and made it possible for women to enter the labour force and earn employment income. By the ninth century, the textile sector occupied between 18%-22% of the entire labour force with women providing between a third and a half of the producers. Females had a monopoly on spinning and sewing delicate clothing and there were no institutional obstacles put in their way: no guilds, no workshops, and no social stigma. The rise in household income motivated society to protect women’s income and, in general, property rights. Islamic law reflects the new social norms that followed changes in the economy.

Use and Abuse

The view that Islamic institutions, legal and economic, were an obstacle to modern economic development in majority Muslim states is the latest significant development in the economic history of medieval Islam. The argument first surfaced in the aftermath of September 11, explaining the attacks by Muslims being frustrated by their historical economic failure. The argument was supported by scholarly output claiming inherently dysfunctional Islamic legal and economic institutions. Since these institutions were formed during the first centuries of Islamic rule in the Middle East, 650-1100 AD, medieval economic history became the symbol of all that went wrong today. In conclusion, the Muslim world will remain inherently inept and hopelessly doomed unless these institutions that prevented economic progress, are dismantled. But is this correct?

As I have demonstrated in my various publications, Medieval Islamic economic institutions rose in response to economic change and developed precisely to accommodate and support economic growth in the Middle East. In themselves and by themselves these institutions were economic growth. The failure to develop modern economic institutions in the pre-modern Islamic world has its roots elsewhere, and has little to do with Islamic institutions. Economic history teaches us that it took the West five hundred years to get to the Industrial Revolution and achieve long-term growth with high living standards. It also teaches us that every other country in Europe, or elsewhere in the world for that matter, failed to follow the transition to modern standards of living achieved by Western Europe. This is the reason why economic historians refer to the ‘West and the Rest’, or the ‘Great Divergence’. Selecting the cultural paradigm as the cause of Islamic societies’ current economic stagnation is a false paradigm with no empirical support. It is an abuse of economic history.